Courtesy of the authorI catch fragmented glimpses of my bald reflection in the elevator mirror as I go up, up, up—to a white-walled conference room, where a small herd of well-groomed doctors, all equally inscrutable, awaits. Dr. Cryptic, a top oncologist here at Minnesota's Mayo Clinic, shuffles papers in a file larger than any 34-year-old ought to have. My finger absently traces the Port-a-Cath jutting from my clavicle when he looks at me and asks: You're sure you want to do this by yourself…?

Courtesy of the authorI catch fragmented glimpses of my bald reflection in the elevator mirror as I go up, up, up—to a white-walled conference room, where a small herd of well-groomed doctors, all equally inscrutable, awaits. Dr. Cryptic, a top oncologist here at Minnesota's Mayo Clinic, shuffles papers in a file larger than any 34-year-old ought to have. My finger absently traces the Port-a-Cath jutting from my clavicle when he looks at me and asks: You're sure you want to do this by yourself…? Courtesy of the author

Courtesy of the author

Courtesy of the authorAdvertisement - Continue Reading BelowThe answer is yes. It's always been yes. The first word out of my mouth as a baby was myself. From that point on, my parents engaged in a relentless battle: their instinct to nurture me (as they did my perfectly docile older brother) versus my fight for independence. But even then, my mother and father swore that everything that made me a pain in the ass as a child—the strong will, the determination to make my own decisions—was going to make me an excellent adult.

Courtesy of the authorAdvertisement - Continue Reading BelowThe answer is yes. It's always been yes. The first word out of my mouth as a baby was myself. From that point on, my parents engaged in a relentless battle: their instinct to nurture me (as they did my perfectly docile older brother) versus my fight for independence. But even then, my mother and father swore that everything that made me a pain in the ass as a child—the strong will, the determination to make my own decisions—was going to make me an excellent adult.More From ELLERelated: Broadway Star Valisia LeKae: How My Cancer Diagnosis Changed My Life for the Better

So they lovingly looked the other way, perplexed, as I evolved from an adolescent TV junkie into a nature-loving, hiking, ice-fishing teen who eschewed dance recitals in favor of solo night hikes near our New Jersey home, who swapped prom gowns and heels for tangled hair and fishing gaiters. The only time I recall asking my parents for something, it was permission to skip two weeks of my sophomore year of high school to travel through Eastern Europe to research a play I'd decided to write. Later there were solo road trips to see the world's largest ball of twine and writers' retreats by a frozen lake in northern Minnesota. Contrary to my Jewish roots and my nascent Hollywood dreams—by third grade I'd decided to be a writer—I craved fresh air, dead silence.

Related: How to Reduce Your Breast Cancer Risk

So when the Hollywood writers' strike hit in 2007, six weeks into my first bona fide job in the business as a writers' assistant on HBO's True Blood, I didn't call my parents in a panic. I hastily threw together a backpack and hit a two-day hiking trail. I was gloriously alone. Euphoric—until a few miles in, when my foot got lodged in the roots of an oak, and my entire body crumpled, tearing cartilage, cracking my kneecap in half, and instantly turning my leg three shades of blue.

Four surgeries over the next four years couldn't fix it. And walking on a knee with only 17 percent of its cartilage was searing. But for me, asking for help would have been infinitely more crippling. So I kept plugging away. I wrote my first True Blood episodes. Costumers decorated my canes for premiere parties; actors stole my crutches for sport.

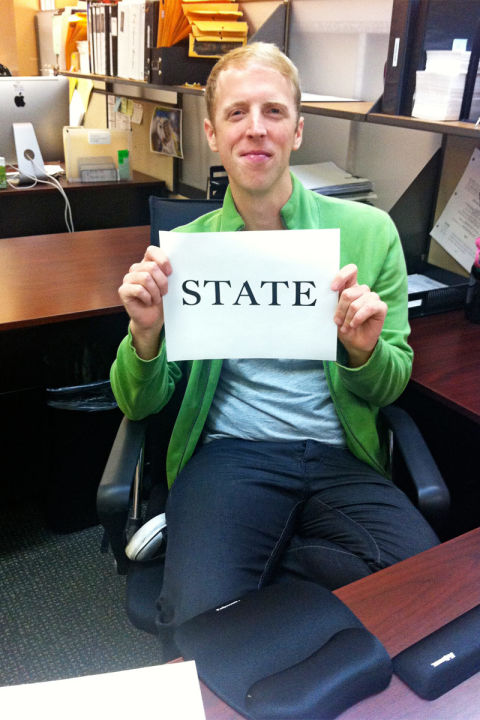

My salve came in the form of TV, of course, in a stack of Friday Night Lights DVDs filled with Coach Taylor's epic speeches about character and beating the odds. In one episode, the team is down, humiliated; the players on the verge of quitting. Coach goes to the locker-room whiteboard and silently writes state—shorthand for the team's ultimate goal, to make it to the Texas state football championships. State was the victory that would make every battle along the way worth it. "State" became the team's battle cry. And, in a very real way, it became mine, too.

Courtesy of the authorLast year, still in pain, I crammed in knee-replacement surgery just before beginning my second season writing for the CW's The Vampire Diaries. I'd expected my surgeon to wake me from my morphine haze to say the problem was finally fixed. Instead he said, "There's something we needed to discuss."

Courtesy of the authorLast year, still in pain, I crammed in knee-replacement surgery just before beginning my second season writing for the CW's The Vampire Diaries. I'd expected my surgeon to wake me from my morphine haze to say the problem was finally fixed. Instead he said, "There's something we needed to discuss."Chondrosarcoma. One of three forms of primary bone cancer. They'd discovered a mass and removed it. So my leg was now fully functional, tumor-free. But a PET scan had revealed a tumor encroaching on my spinal column. "I've never seen anything like this, especially in someone your age," he told me. "Nothing about this is going to be easy."

I sat there, dazed, as he rattled off statistics. Chondrosarcoma is rare as hell: It accounts for less than one percent of all cancers, and the average age of diagnosis is 51—it's almost unheard of at my age. Mine was grade three, fast growing, which instantly placed me in the "poor" prognosis column and at high risk for recurrence. Worse, chondrosarcoma tends to defy conventional chemotherapy and radiation. Surgery is usually the best option, but my tumor had grown far enough into my spine that removing it carried a high risk of paralysis. Chemo might not work, but it was still my best chance. And I needed it immediately.

Ironically, chondrosarcoma wasn't necessarily the reason my knee hadn't healed—cartilage is incredibly difficult to regenerate under any circumstances—but the injury was the only reason they found it. "You're lucky we were looking in the first place," the doctor said. I was still digesting the juxtaposition of rare cancer and lucky when my mom entered the room, cutting him off. When he left, I told her the knee replacement had worked. And that's all I told her.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

没有评论:

发表评论